|

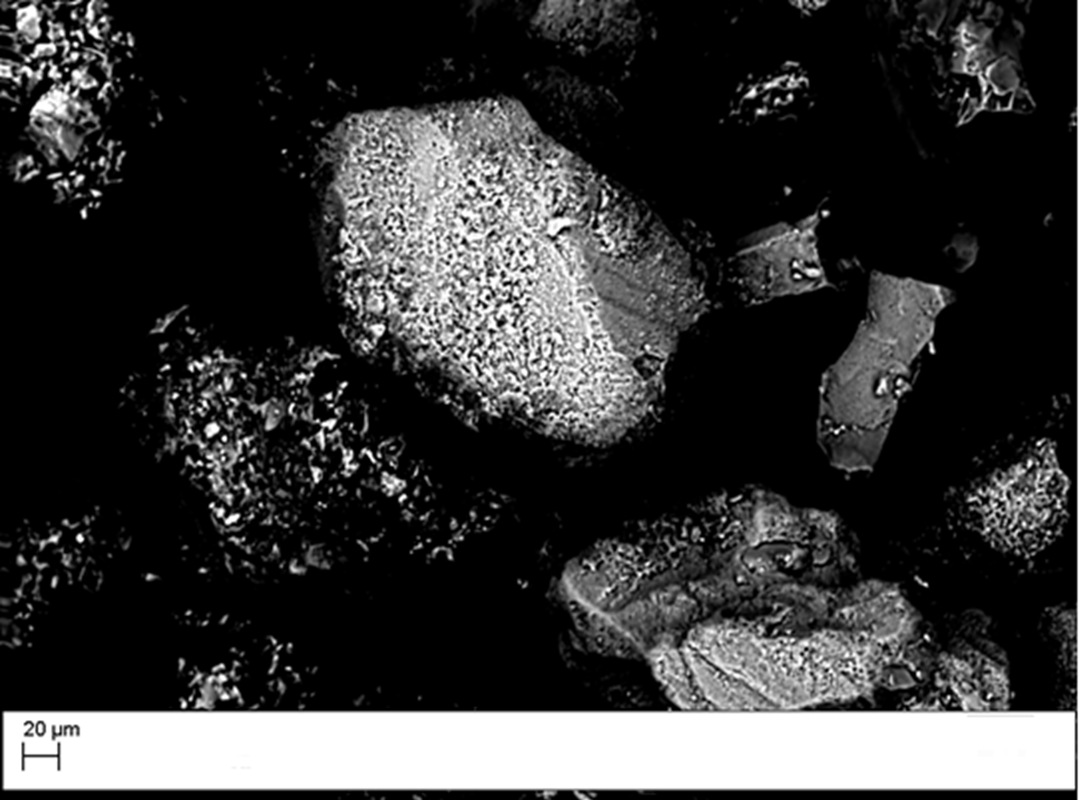

By Thiago Silva, University of Stirling, and Sam Hughes, Forest Research. Around 13 thousand hectares of newly created woodland were reported in the UK for just 2022/23 [1], an area roughly the size of Bristol. Monitoring the development of these woodlands through field work alone would be a massive endeavour, as highlighted last year by Laura Braunholz on this very blog. So as part of our research in TreE_PlaNat, we are also testing a different approach for monitoring woodlands – by shooting lasers at them. Seeing the world from above using dronesTraditionally, satellite imagery has been used to monitor large extents of woodland and other habitats, but it has some limitations. The best freely available imagery, from the Sentinel-2 platform, gives us images with 10 metres per pixel - to go beyond that we would need to purchase expensive, commercial satellite imagery. Moreover, satellite images can be obscured by clouds, which may be a bit of a problem for monitoring land surface in the UK… Drones have exploded in popularity as consumer devices for video and photography, but have also revolutionised the way we use images for studying woodlands and restoration [2]. Fairly good aerial mapping can be done using off-the-shelf drones costing £500 - £1000, and a very capable, mapping-specific drone paired with a high-precision GPS system (for increased mapping accuracy and repeatability) can be had for less than £10,000. That will give you the ability to map up to 200 hectares (almost 500 acres) in a single flight of about 40 minutes, with a pixel size of about one inch per pixel. Especially when we consider the size of most new woodlands, the difference between drone and satellite imaging is stark. Here is a comparison between a drone airphoto and a Sentinel-2 image of one of TreE_PlaNat’s woodland sites. You’d be hard pressed to even tell there was a woodland there based on the satellite image alone. But even with this amazing level of detail, all we get from aerial photography is the top of the canopy. This is useful for mapping woodland extent, identifying individual tree crowns and gaps, and maybe even picking up species. But when it comes to monitoring woodlands, the vertical component of the canopy is very important. How tall are the trees? How dense is the canopy? How much understory vegetation is there? This vertical complexity is a key component for understanding habitat quality, carbon stocks, and the overall quality and health of a woodland. Beam me up... I mean, down!To overcome the limitations of aerial photography, enters LiDAR. An acronym for Light Detection and Ranging, LiDAR works in a similar way to radar (Radio detection and ranging) and sonar (sound navigation ranging). We know radio waves travel at the speed of light, and sound waves at the speed of sound, so by sending out a radio or sound pulse and precisely measuring the timing of its echo after bouncing on a surface, we can tell how far the surface is. The same principle applies to LiDAR, but what we are sending is a laser beam instead – which gives us pinpoint accuracy. LiDAR sensors will send thousands of beams per second in multiple directions, and each beam will pinpoint the position of what/where it hits, creating the main output of a LiDAR scan – the point cloud. Lidar point clouds can range from thousands to billions of points, depending on sensor characteristics, area covered and scanning distance. LiDAR is ideal for creating 3D models of woodlands, as the narrow beams can go through tiny gaps in the canopy and hit different parts of the trees – some even reaching the ground. The technology itself is not new – the first developments came in the early 80s, and by the late 2000s LiDAR was already in regular use for both research and commercial forestry [3]. Still, until very recently LiDAR sensors would cost from a few hundred to about a million pounds. And being large and heavy sensors, they needed a crewed airplane to fly them – which are also very costly to obtain and operate/maintain. The rise in drone technology and the push for cheaper/smaller lidar sensors for self-driving cars and navigation in general created the ‘perfect storm’ for a new generation of laser scanners, called solid-state LiDARs. These are cheaper and simpler to manufacture and are much smaller and lighter as they require fewer moving parts. They do trade off some range and accuracy for this, but that means a fully capable drone system equipped with a LiDAR sensor and GPS station can be had for less than £30,000, at least 10x cheaper than the previous generations of LiDAR drones. Add in another £1,000 for pilot training and certification, and a few thousand more for a good PC and required software. But once you have the system, the cost of flight is only the cost of getting to the site, plus the energy cost for charging the batteries. A drone-mounted LiDAR system also has the advantage of flying much closer to the canopy and at a lower speeds, meaning it can cover the surface with a lot more beams. Airplane-based LiDARs will be flown at 500-3000 ft, yielding about 20-50 points per square metre, while our drone flies at 200-400ft and yields between 100-200 points per square metre. Airplane LiDARs still have the advantage of covering very large areas at once, while drone coverage is limited by battery life and flying regulations. Looking inside the woodlandOne useful way to look at LiDAR data is by taking a cross-section (a ‘slice’) of the point cloud, so we can look at it from the side. On the figure below, the red line shows the direction of the slice on a top and a perspective view of the point cloud, and the actual slice is shown at the bottom. It is easy to see there how, from left to right, we transition from a more mature, taller woodland to an open gap with a single standing dead tree, and then to a younger stand with shorter and denser trees. We can also see where the beams hit the ground, revealing the curved shape of the underlying terrain. Although we can understand a lot about the structure of each woodland by just looking at the full 3D point cloud and the different slices, to be more consistent and repeatable we also try to be quantitative about it. Over the years, scientists have devised several lidar metrics, calculations based on the position and distribution of points, which enable us to measure and compare different woodlands. One of the most basic metrics is the actual canopy height. To obtain it, we can’t just measure the tops of the trees in the point cloud. A shorter tree at a higher elevation would seem taller otherwise. So one of the first steps when processing LiDAR data is to isolate ground points and interpolate them to create a Digital Terrain Model (DTM), a representation of the ground surface as if it was bare. We can also interpolate the top points of the point cloud to generate a Digital Surface Model (DSM), as if we draped a cloth on the land surface and followed its contours. We can then subtract the DTM from the DSM to get a Canopy Height Model (CHM), a representation of the woodland as if it was standing on perfectly flat ground. From the CHM, we can then calculate the height of every tree, and see how tall the woodland is on average, as well as how variable tree heights are. Tree height is strongly associated with woodland age and with wood volume and carbon stocks, so it is a very important metric. Other metrics will look at the vertical complexity of the woodland, for example by looking at how skewed the distribution of point heights is towards the top or bottom of the woodland. A point cloud where most points are clustered at the top means a dense canopy with no underbrush, while a more even distribution means there is a well-developed subcanopy. A grassland with sparse trees would be skewed towards the bottom, as most of the plant mass is close to the ground. And we have even more creative metrics, such as the ‘rumple index’ (we always chuckle saying it). It is calculated is by estimating the total surface area (again, imagine a cloth being draped over the woodland, and then measuring the area of that cloth), and then dividing it by the corresponding flat ground area. A high number will mean a very, well…rumpled surface with lots of consecutive ups and downs, meaning a woodland with trees of uneven height and lots of gaps. A smaller number means a more even, ‘tidy’ surface, for example for a planted tree monoculture.

As we also took measurements of habitat structure on the ground, measuring tree stem density and diameter at breast height (DBH) in plots across our sites, we can compare drone metrics with field-based assessments. At TreE_PlaNat, we are using these metrics to compare how naturally colonized, planted, and mixed woodlands differ in their structure, and consequently, their habitat quality and complexity. To see some of our early results and ask any questions you may have, watch our webinar (held 17th May 2024) here.

0 Comments

Reflections following the Oxford Real Farming ConferenceBy Susannah Fleiss, University of Edinburgh. In early January, I attended the Oxford Real Farming Conference (ORFC), which has grown rapidly since its beginnings as a small gathering in 2010, this year welcoming 1,800 delegates in person. The majority of conference attendees are farmers interested in agro-ecology, producing food with nature at the heart of their farming systems. Such ‘land sharing’ systems, where nature and food production go hand-in-hand within a landscape, create and maintain many of the semi-natural and mixed habitats that represent and support much of the nature in Britain. We often hear that these systems would not succeed in ‘feeding the nation’, as a justification for unsustainable, intensive farming methods. But, with widespread dietary change to adapt our consumption to the products of this type of farming, we Britain could indeed feed itself through low-input, sustainable farming methods, whilst supporting biodiversity in the same landscapes [1]. Broadly speaking, the farmers who attend the ORFC are likely to be interested in supporting trees and woodland on their land, for a whole host of reasons. Yet, in spite of 19 parallel sessions running through the two-day event, there was very little that brought trees and woodlands into focus. To make up for this, here I take the opportunity to reflect on the question: how might natural colonisation fit into these farming systems? And alongside this question, perhaps – should it fit? In this blog post, I will bring together my thinking about natural colonisation, following the first year of working on this project (particularly in light of many interesting discussions with our Knowledge User Board and other stakeholders), alongside my own start as a small-scale farmer. What biodiversity does natural colonisation bring to farms and landscapes? Before musing on how natural colonisation could fit on farms, it would be useful to consider what it brings to a landscape. From our early project work bringing together some case studies of natural colonisation [2], it is clear that natural colonisation provides valuable habitat both in the early scrub stages (as at Noddle Hill, where succession has not yet progressed beyond scrub [3]), and once a closed canopy woodland begins to form (for example, at Monks Wood or Hucking Estate [4,5]). Woodland resulting from natural colonisation may have better ecological condition than planted woodland (such as through greater structural diversity, and greater resilience of the locally-adapted trees). In this blog, however, I mostly consider the early habitat phase of natural colonisation, as this is what farmers would be faced with first - and it can sometimes last for decades! As a starting point for understanding the biodiversity value of any particular habitat within our landscapes, I like to consider it from two perspectives: its equivalents both in prehistory and in traditional farming systems. It goes without saying that all prehistoric forest was formed through natural colonisation! Across much of Britain, it’s likely that scrub and open woodland would have formed part of the prehistoric ‘wildwood’ habitat mosaic, alongside closed-canopy woodland and grassland, following the lines of thought of Oliver Rackham and Frans Vera [6,7]. We don’t know what proportions of our prehistoric landscapes were occupied by these different habitat types, but judging by the extremely high levels of biodiversity supported by extensive scrub and young/open woodland habitat today, such as at Knepp Estate, these habitats would have played an important role in supporting a rich flora and fauna across wider landscapes [8,9]. Agriculture became widespread in Britain during the Neolithic period, and major changes to landscapes and biodiversity occurred. However, it wasn’t until the more recent transition from traditional, pre-industrial farming systems to industrialised farming that detrimental, pervasive biodiversity loss occurred in Britain – largely over the last 200 years, but particularly since 1950 or so. Traditionally-farmed landscapes produced food, fuel and fibre for their human inhabitants, whilst supporting biodiversity, so can today provide us with opportunities to explore how production and nature might go hand-in-hand. It is also worth remembering that standards of living pre-1700 were often far below what would be considered acceptable today, and the number of mouths to feed was much smaller (yet here I refer again to the Sustainable Food Trust’s report on feeding today’s Britain with sustainable local produce [1]). In traditionally-farmed landscapes, areas of scrub and heathland were used for firewood, other fuel collection, and common grazing (although many commons likely had higher grazing pressure historically than today, so perhaps would have been more open) [6]. Hedges were generally much taller, wider and denser than those of today, through necessity of being stock-proof, and provided linear scrub-like features across farmed landscapes. I also wonder to what extent coppice regrowth (previously so widespread across much of Britain) produced a habitat that was similar in ecological functioning to the scrub and young, open woodland that is formed in the early stages of natural colonisation. This undoubtedly only touches on a few of the historic roles of scrub and open woodland in landscapes… In comparison to the mixed landscapes of previous centuries, many of today’s landscapes in Britain are dominated by a few habitat types alone, often of low biodiversity value. Open woody habitats and scrub are largely missing in many areas, with many marginal habitat areas (such as previous heath and scrub patches) now farmed, and woodlands no longer coppiced. Field sizes have increased, thanks to the removal of hedgerows, and most hedges are cut back to short and narrow dimensions each year. In many places, this has resulted in a thorough removal of scrub and young, open woodland from our landscapes. Why might farmers want to create woodland through natural colonisation?

When creating woodland, farmers would have particular aims in mind – for example, producing firewood or timber, providing shelter for stock or crops, helping manage water in the landscape, supporting biodiversity on the farm, and/or (as of fairly recently) sequestering carbon. There are three particular difficulties with the idea of using natural colonisation rather than tree planting to create a woodland on a farm. Firstly, natural colonisation is a slow process, taking some decades to form a woodland. Secondly, the outcome cannot be predicted: sometimes trees don’t colonise, and if they do, the species mix can’t be guaranteed. Thirdly, it’s not clear what saleable goods (wood, timber and potentially other products) would be produced, nor quite how many generations it might take! However, natural colonisation can lead to the eventual creation of mixed-structure woodlands of locally-adapted trees. Of course, many ‘goods’ produced by habitats on farms are not saleable, but come in the form of ecological or environmental benefits. The initial scrub habitat formed by natural colonisation might support pollinators (particularly through flowering blackthorn and hawthorn), provide shelter and regulate the farm microclimate, help attract wildlife to the farm for natural pest control, or help keep unwanted wildlife separate from other areas of the farm. One farmer I know attributes his avoidance of bovine TB to 6m-wide hedges, which provide ample habitat for badgers and other transmitters to use without interacting with the cattle. Browse (fodder from woody shrubs/trees) has high nutritional value for livestock [10], so natural colonisation could provide sheltered areas for livestock to occupy and feed on (provided stocking were infrequent enough to allow the scrub and trees to develop). As interest in carbon sequestration grows, use of farmland to sequester carbon is becoming an increasingly hot topic. The capacity for natural colonisation to sequester carbon is unclear – certainly, areas of tree planting would store aboveground carbon (i.e. woody biomass) more quickly. However, the soil disturbance from tree planting can cause substantial carbon emissions, and the same may be true for natural colonisation, although perhaps to a lesser extent [11,12]. At this stage, it’s likely that supporting biodiversity and future resilient woodlands would be the main reasons for allowing natural colonisation, rather than carbon sequestration – but we’re eagerly awaiting more information in this field. Farmers (and other land managers) will have diverse opinions about when natural colonisation might be an appropriate use of land, which we will have much more information on once the results from the TreE PlaNat nationwide survey. There are a few key challenges that may crop up, such as the uncertainty of the outcomes of natural colonisation, and the ‘untidy’ appearance of scrub, which is not generally considered farmed land – what might the neighbours think?! Is the priority to establish a closed canopy woodland quickly? We look forward to knowing more about land managers’ preferences for different woodland creation methods as the project progresses. Where next? Are we asking too much of farmers? From observing the current round of consultations for Wales’ new Sustainable Farming Scheme, my feeling is that an awful lot is being asked of farmers here, and in other nations too. But, given our unprecedented circumstances of biodiversity and climate crises, poor national health, potential disruptions to long supply chains, and the urgent need to increase our consumption of local produce, this is probably to be expected. I would hope that amongst all these demands on land, the odd untidy corner will be allowed to do its thing on most farms. Other measures, such as improved hedgerow management, to encourage larger and denser hedges (saving costs and increasing shelter at the same time!), and potentially coppicing woodland (could we produce our own fence posts?), could also provide related biodiversity benefits. There are many disputes around the proposed eligibility criterion of 10% tree cover on ‘plantable’ areas of a farm for the upcoming Sustainable Farming Scheme (among a number of other requirements). This shows that good communication and messaging is key, and suddenly imposing requirements on farmers may not go down well. There are still lots of unknowns about the best ways to manage land for productivity and biodiversity, in the context of major changes to climate and society, and how to have constructive conversations around this. I look forward to continuing the discussion. CITED LITERATURE: [1] Sustainable Food Trust (2022) Feeding Britain From the Ground Up. [2] Fleiss, S. and TreE PlaNat Knowledge User Board. Factsheet: Case studies of woodland creation through natural colonisation. [3] Broughton et al. (2022) Slow development of woodland vegetation and bird communities during 33 years of passive rewilding in open farmland. PLOS ONE 17(11). [4] Broughton et al. 2021. Long-term woodland restoration on lowland farmland through passive rewilding. PLOS ONE. [5] Woodland Trust (2019) Hucking Estate Management Plan 2019-2024. [6] Rackham, O. (1986) The History of the Countryside. [7] Vera, F. (2000) Grazing Ecology and Forest History. [8] Tree, I. (2018) Wilding. Picador. [9] Mortimer et al. (2000) The Nature Conservation Value of Scrub in Britain. JNCC Report no. 308. [10] Agricology: Browse, preserved tree fodder and nutrition. [11] Friggens et al. (2020) Tree planting in organic soils does not result in net carbon sequestration on decadal timescales. Global Change Biology 26(9). [12] Street, L. and Housego, N. (2023) Presentation: Soil carbon, climate and land use. University of Edinburgh Forests and Landscapes Network event. Growing an arboreal solar system: a call for land managers to to take the TreE PlaNat survey2/5/2024 By Rachel Orchard, Forest Research

Each tree is like its own planet. From the canopy of each tree, you’re given a new view of the Earth below. From the ground, you can look up into a web of branches that form the contours of its unique terrain. Beyond sight, each tree has its own sensory quirks, just like a planet - with rough or smooth bark, like bumpy or flat ground, and distinct smells, like a mini atmosphere. Looking at a collection of trees is like looking at an arboreal solar system, sometimes with uniform sized tree planets, sometimes with tree planets of all shapes and sizes. Unlike planets, trees are rooted to the same spot on this Earth. But how did each of these tree planets come to be rooted where they are? Did a human help by planting a sapling that started its life in a nursery? Or did natural colonisation lead it to its’ rooting spot? The unique history of each tree can be divided into these two methods of establishment, planting or natural colonisation. However, when scaled up to a woodland level, the history of a group of trees could also be a mix of these methods, known as a hybrid approach to establishment. Whatever the scale, it is up to the custodial land managers to choose which of these establishment methods is best suited to the land and their objectives. The TreE_PlaNat research project, led by University of Stirling and in collaboration with partnering organisations*, is investigating the social and ecological factors behind land manager’s decision-making on these methods for woodland expansion. Here the alternative meaning (and spelling) of ‘PlaNat’ refers to the methods of Planting and Natural colonisation. As a social scientist at Forest Research, I work on the social side of the project and we currently have a national survey live to ask all types of land managers about which methods they would choose and why, if they were to expand a patch of woodland. If you are a land manager, please share your knowledge and experience on the topic by donating 15-20 minutes of your valuable time to complete our survey: https://peopleandtreesurveys.limesurvey.net/593382 Understandably, you may ask why should I? You must be aware of the ambitious tree planting targets set by UK government. This clearly indicates that the default method for growing more trees is with human assistance, which means most of the policy, grant schemes, and procedures are set up with this method in mind. This begs the question: what about growing trees naturally? As neutral researchers, we need to know what method land managers would choose because this research will inform the next wave of policy thinking and the ripple effects across funding schemes and practitioners. This will impact the next generation of land managers and the establishment of future arboreal solar systems. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that our results accurately reflect the views of all types of land managers, with many different objectives that would influence their choice of tree establishment method. To clarify, when I say all types of land managers, we want to hear from anyone that identifies as one of the following:

If you identify as a land manager but do not feel that you fit into one of these categories then there is an ‘other’ box too. Here’s the survey link once more in case you missed it: https://peopleandtreesurveys.limesurvey.net/593382 If you’re not convinced already - there is also a prize draw! Thank you for helping to shape the future arboreal solar systems! 😊 By Laura Braunholtz, University of Stirling When it comes to new areas of woodland, questions remain about the extent to which the way they are created plays a role in shaping their structure, biodiversity, and functioning. Is it always true that woodlands that are created through planting will have a more homogeneous form and structure compared to naturally colonised ones? Are trees within naturally colonised woodlands more resistant to disease than those in planted areas? Do woodlands formed through different processes provide habitat for the same species of wildlife? In trying to answer these questions and more, myself and two field researchers, Megan Layton and Billy Dykes, found ourselves crouched in a thicket of blackthorn under the blazing mid-June sun, tape measures and clipboards in hand. It was unfortunate that the random number generator had directed us to this particular location, but as we quickly learned, in young naturally colonised woodlands you’re never too far from spiky vegetation. This was during the summer of 2023, and our team of three was carrying out the ecological fieldwork for the TreE PlaNat project. We conducted a range of surveys across our study woodlands, involving multiple trips to each site between May and September. Marking the boundaries of our quadrats, while avoiding the spikes! Preparation is key Getting to the point of carrying out the surveys had taken considerable preparation. Risk assessments, protocols, purchasing equipment, and, of course, the all-important site selection process. Selecting the woodlands that made up our study locations involved months of reviewing the long list of potential sites, poring over maps and satellite images, consulting Woodland Grant Scheme datasets, comparing notes with colleagues at Forest Research, and the challenge of tracking down landowners and managers to gain permission to carry out our surveys. The resulting list of 28 sites was spread across central and southern England. We kept a number of properties consistent across our sites; they were all relatively young woodlands, ranging from 15-30 years old, adjacent to areas of established woodland and on land that had previously been arable or improved grassland. Seven of our woodlands had been planted, nine were sites of natural colonisation, and twelve came under our “mixed” category, having a combination of planting and natural colonisation processes at play. Into the wilderness we go Now we were carrying out our surveys, collecting data on several metrics that we had chosen to represent the structure, ecological function and biodiversity of woodlands. This included setting out five 20m diameter plots at each site, within which we were identifying trees, measuring their diameter at breast height (DBH) and counting seedlings and saplings to assess tree biomass and habitat complexity. We also assessed the trees for signs of disease or pests, focusing on those of highest concern (further information: Observatree). We checked a sample of leaves from ten trees in each plot for signs of damage by insect herbivores and recorded the number of seedlings and saplings that had been browsed by mammal herbivores. Using 20 plasticine caterpillars at each site, we quantified predation pressure on insect herbivores. To quantify the biodiversity value, we were assessing several different taxonomic groups. In small quadrats, we looked at herbaceous vegetation, poring over keys and guidebooks to identify species of grass, ferns and other flowering plants. We set out camera traps to document sightings of mammal species and placed acoustic recorders in trees to capture the sounds of passing insects, birds and bats. On two different nights during the summer months, two moth traps were set up at each site and Billy had some very early morning starts to check the traps, identify the species within, and release all moths on site. For the final surveys in August, Dr Thiago Silva flew a drone mounted with a LiDAR sensor over all the sites to capture information about the structure of the woodlands. A selection of TreE PlaNat surveys: Heath light trap for moths, AudioMoth acoustic recorder, and plasticine caterpillar with evidence of bird pecks Data, data, data

Reflecting on the field season now, summer seems a distant past, and November’s short, cold days see me sitting at my laptop writing code to crunch the numbers and try to answer our research questions. We collected an impressive amount of data, measuring over 5000 trees from 36 different species, as well as counting over 1000 seedlings and saplings from 24 tree species. We captured nearly 2500 moths from 398 species and identified over 130 species of herbaceous ground flora. The camera trap and AudioMoth data files are still being processed; soon, we’ll know more about the mammals and bird species using our woodland sites. Data analysis might not sound as glamorous as frolicking among the trees, but it's the key to understanding the intricate ecological dynamics at play within these ecosystems. Spoiler alert: nature's spreadsheet is a lot messier than Excel. Check back soon to find out what we’ve learned! New resource available: collection of case-studies of woodland creation through natural colonisation By Susannah Fleiss, University of Edinburgh

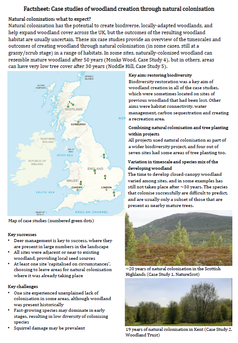

How can landowners try something new, when little information is available? Stimulated by conversations among foresters, farmers, land agents and ecologists, the TreE PlaNat team have put together a number of case studies on woodland creation through natural colonisation to address this issue. When creating woodland, land managers (such as farmers, foresters, estate owners and their land agents) usually plant trees, designing the planting scheme according to their local context, reasons for creating the woodland, planned uses, and desired species. However, allowing trees to establish through natural processes can create locally-adapted, resilient woodlands, of high biodiversity value [1]. When creating woodland through ‘natural colonisation’, seedlings germinate from local seed sources that arrive at the site naturally, some of which survive and develop into trees. A key difficulty for land managers is that the outcome of this process is not guaranteed: it is very difficult to predict the timeframe it takes to create a closed-canopy woodland, and the species which will colonise the area and survive [2,3,4]. Our project, TreE PlaNat (Treescape Expansion through Planting and Natural colonisation), is examining how, where and for whom natural colonisation might be used to create new woodlands, including in combination with tree planting. As part of this project, researchers at the University of Edinburgh are facilitating a ‘Knowledge User Board’ of land managers, who provide feedback on the research directions and findings, and help guide the project to produce useful outputs for those working on the ground. Early in the project, the group highlighted the importance of having case studies to provide land managers with examples and basic knowledge to consider using natural colonisation to create woodland. In a collaborative effort with the Knowledge User Board, we created a collection of case studies and one-page summary factsheet, available through the Edinburgh Research Archive and the TreE PlaNat website. By Maddy Pearson, Forest Research On a sweltering Thursday in June, we headed to the Hall Farm Estate on the southern fringe of Dartmoor. We were a small team of two social scientists and one ecologist from Forest Research. Our visit was an opportunity to engage with colleagues from the Forestry Commission and The Woodland Trust on the topic of natural colonisation. Chauffeured by a Forestry Commission colleague, we weaved through country lanes, admiring overhanging trees and rolling hills before arriving at a picturesque farmhouse. The farm and its woodland were steeped in history, having been home to The Woodland Trust’s founder Ken Watkins during the Trust’s inception. In recent history the farm had been in private ownership, but has this year been bought back by the Woodland Trust. Dave Rickwood, The Woodland Trust’s site manager for Dartmoor, explained that the Trust are looking into an England Woodland Creation Offer (EWCO) grant to undertake natural colonisation on the Hall Farm Estate.

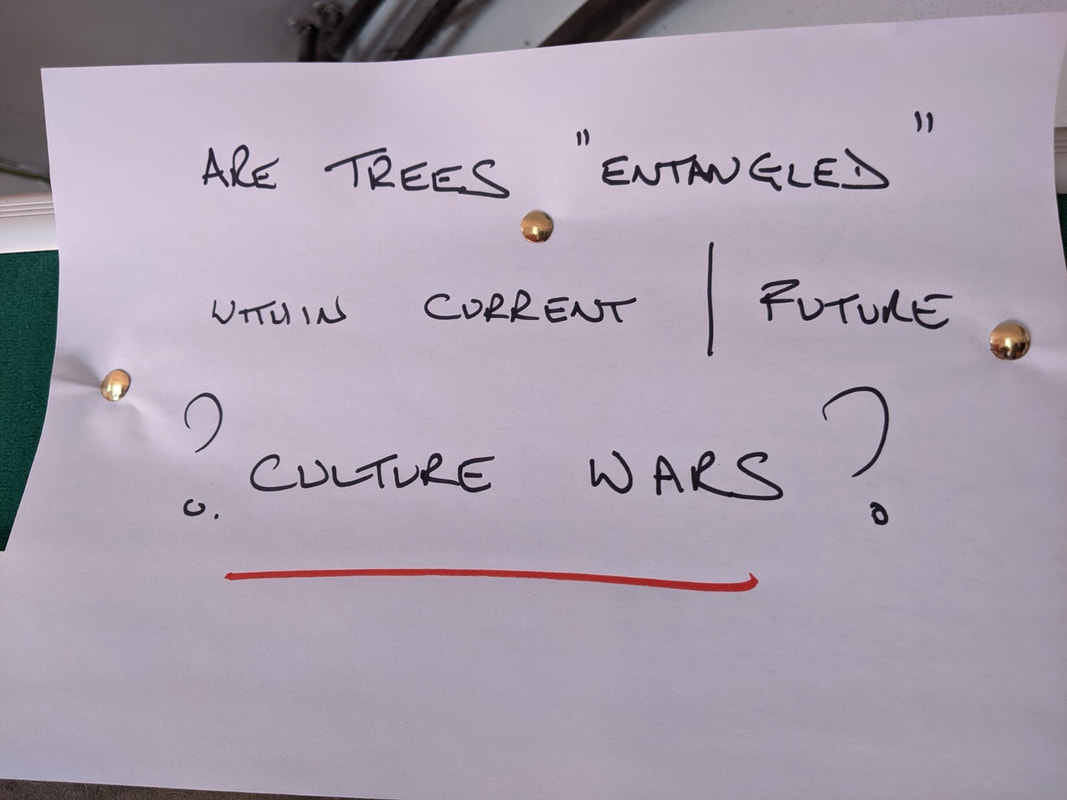

A final piece of paper caught the eye of one of the researchers. In black felt-tip pen the text asked of the reader, “Are trees “entangled” with current/future culture wars?” This is certainly a question worthy of attention, and not only for the social scientists among us. Tree cover expansion as an ecological process can never be separate from the socio-cultural, the economic, or from the wider environmental politics of the day, and this must be recognised and taken seriously if national aims are to be met. How should land be used? How should the climate crisis be responded to? These are the kinds of questions that emerge in present-day culture wars, and are the questions to which tree cover expansion can be considered “entangled”. Presenting our researchBefore heading out to see natural colonisation beside the estate, we presented some of our research to date, and introduced questions we will be exploring over the next year. As well as the importance land managers place on outcome uncertainty when weighing up whether to use tree planting or natural colonisation as tree cover expansion strategies, we landed on the importance of language and communication. Recognising that uptake of grants for natural colonisation has been low, and that natural colonisation as a term is not commonly used by land managers, we asked attendees on the visit to consider how language and communication might be impacting the tree expansion strategies taken up by land managers they work with. With this provocation in place, the group of attendees, as well as three eager dogs, headed out of the barn to see some trees! Heading up the hillWe were led away from the barn through the farm to see examples of natural colonisation on Yadsworthy farm. We took in the tree cover that was gradually creeping up the hill and were asked to estimate, for a big reveal later in the day, how long it had taken for this colonisation to occur. Asked about any pressures on natural colonisation in this area, Dave explained that periodic grazing is used in the field to trample any unwanted vegetation. He said mortality is good given low deer pressure in the area, although he did explain that this is changing as these colonised fields are starting to provide optimum habitat for deer, and thus they are starting to see higher numbers appear. To Dave’s surprise he has even spotted red deer recently. This observation really brought home that natural colonisation is part of more-than-human assemblages that are dynamic and will continue to change as tree cover increases. We continued on up to the fringe of Dartmoor national park and Dave shared an interesting finding with us from a researcher at Plymouth University. This professor has estimated that for woodland expansion to occur on the commons of Dartmoor, 8 years of no grazing would need to be secured. Grazing pressure is just one of the many things landowners weigh up when deciding on woodland expansion strategies. Where it all beganAfter a short lunch pitstop back at the barn we headed out of the farm in the opposite direction to see the natural colonisation that had been making its way up the hillside from the viewpoint of its seed source. We walked along a country lane, turning sharply left onto a narrow footpath that allowed us to walk beside the River Erme. We came to a standstill a few minutes later underneath the riparian woodland, listening to the sound of water cascading through the channel below us and noting how inviting this river looked given the hot weather. Dave explained that a variety of trees were colonising the land from this riparian strip up the hill, including Sessile oak, hawthorn, holly, hazel, rowan, sycamore, beech, alder buckthorn. Having waited in anticipation, Kevin explained to the group how long it had taken natural colonisation to reach this level of maturity. Using maps and aerial footage from the post-World War Two period, the team of spatial scientists at Forest Research had estimated that natural colonisation had taken about seventy years to reach its current state. We all agreed that while the tree cover was impressive this was quite a long time! The time it takes for natural colonisation to establish has emerged as an area of concern across land manager groups and this example certainly spoke to concerns that establishment could take longer than a human lifetime. That said, standing among the plush trees you couldn’t help but be struck by the diversity and beauty of this naturally colonised space and see the appeal of using such strategies.

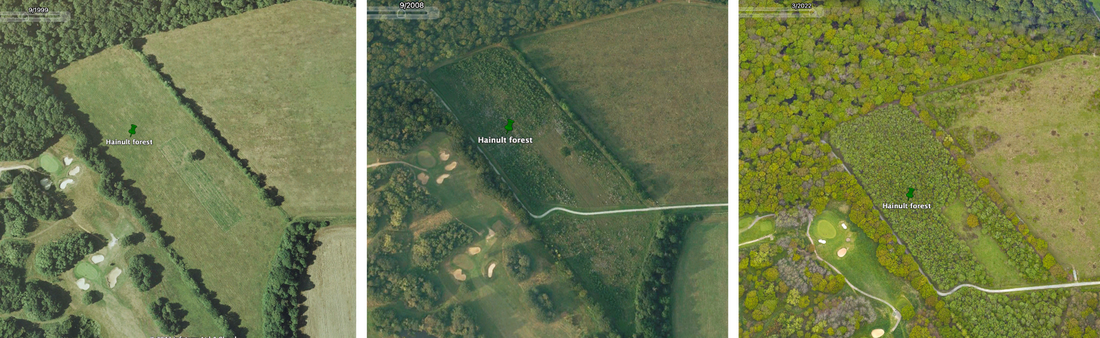

We walked back up to the house, discussing our research and planning to follow up with some new faces we had met. It was a stimulating and thought-provoking day out, one that sparked conversation in the car back to Plymouth around what kind of site we might like to see next. We wondered about a visit to a site where natural colonisation has been given the green light but is yet to begin. Or, we thought it might be interesting to visit a site where natural colonisation had failed. We sunk back into the warm seats of the car and decided it was a decision for another day. By Elisa Fuentes-Montemayor, University of Stirling Tree planting has been the most common woodland expansion strategy in the UK for more than a century, but recently there has been a renewed interest in incorporating natural colonisation as an alternative or complementary approach. But it is not always clear under what circumstances natural colonisation is likely to be and appropriate woodland creation method, or what the likely outcomes of this approach are and how do these compare to those of tree planting. In this article, we explore how, where and for whom these different strategies can be used to scale-up woodland creation on agricultural land. WOODLAND EXPANSION Woodland expansion is widely regarded as a key part of the solution to counteract climate change and aid biodiversity recovery. This is because woodlands and trees can sequester carbon from the atmosphere and also provide habitats for many wildlife species. Expanding tree cover has therefore made its way to the forefront of the current environmental agenda, nationally and internationally. In the UK, tree planting has been the most common woodland expansion strategy for more than a century and is expected to continue at an accelerated rate in the decades to come, with the UK Government pledging to plant an additional 30,000 ha of trees per year up to 2050. Tree planting is generally a quick and reliable method for establishing woodland. However, there are challenges associated with scaling-up tree planting at the level required to meet current targets, for example due to insufficient availability of locally sourced seeds/planting stock and a shortage of skills in the forestry sector. But planting is of course not the only way to create and expand woodlands, and recently there has been a renewed interest in incorporating natural colonisation – allowing trees to colonise new areas naturally – as a complementary strategy for large-scale woodland expansion in the UK (natural colonisation not to be confused with natural regeneration – the establishment of trees from seeds germinated in-situ – which is a key process underlying the long-term continuity of existing woodlands). However, we still have a poor understanding of when and where natural colonisation could be a viable and appropriate strategy for creating woodlands, and of what the relative benefits and drawbacks of these alternative strategies might be. TO PLANT OR NOT In general, planting seedlings/saplings is considered a quicker and more reliable method for establishing woodland than allowing an area to be naturally colonised by trees. The success of natural colonisation is largely context-dependent and strongly influenced by a variety of factors. One of these is proximity to seed sources such as nearby mature woodland or other trees; the density of naturally established trees typically peaks at 20-30 m from seed sources; it then progressively declines at longer distances up to ~150 m, being mostly dominated by wind-dispersed seeds of species such as birch and willow. Bird-dispersed seeds of species such as rowan and cherries can still colonise in large numbers at long distances from existing seed sources. Species with heavier seeds dispersed by gravity or mammals (e.g. beech) are usually slower to colonise. Local soil conditions to enable germination are another important factor; in general, natural colonisation is more readily achieved on sites with nutrient-poor and well-drained soils where competing vegetation is sparse (unlike agriculturally improved sites with fertile soils where competitive vegetation can hinder the germination and on-going growth of woody species). Herbivory pressure also plays an important role; whilst this is strongly landscape-dependent, in most instances, grazing and browsing pressure from livestock and other animals such as deer and rabbits will have to be substantially reduced at least during the early stages of natural colonisation to achieve sufficient levels of tree establishment [1,2]. WAITING TIMES In planted sites, canopy closure typically occurs within 15 years. But despite initial tree establishment happening relatively quickly, it can take decades or even centuries for planted woodlands to eventually develop some vegetation characteristics similar to those of mature ancient woodlands [3]. The length of time for trees to establish via natural colonisation on abandoned agricultural land is far more variable. Some studies have shown that natural colonisation can happen relatively quickly, but that if it does not take place within the first 5-10 years then the process can be extremely slow, taking 30-70 years for a sparse and patchy cover of trees to establish. A recent study documenting the natural colonisation of two former agricultural sites in eastern England reported that vegetation establishment was relatively rapid, with 86% tree cover averaging 3m height within 23 years, and 100% tree cover averaging 13m height after 53 years, when the vegetation structural characteristics of one of the sites were approaching those of nearby ancient woodlands. However, the tree species composition of these naturally-colonised sites was still different, being dominated by clusters of animal-dispersed species such as oak and hawthorn and wind-dispersed species like ash occurring near adjacent woodland [4]. In general, it is expected that pioneer species such as birch, willow and hawthorn are likely to dominate in the early years of natural woodland establishment, with a gradual transition to more shade-tolerant species as the site develops. In contrast, planting allows more control over the mixture of species, the density and spatial arrangement of trees present on a site from the onset. THE RELATIVE BENEFITS Existing evidence on the consequences of woodland creation in the UK is dominated by studies of coniferous plantation woodlands, and much less is known about the effects of planting semi-natural woodlands on agricultural land (which covers over 70% of the UK and holds the greatest potential for woodland creation). The limited evidence that we do have shows that the benefits of tree planting include enhanced habitat connectivity, biodiversity value, ecosystem service provision such as flood mitigation, and economic paybacks derived from timber or carbon credits. Knowledge about the ecology of naturally colonised woodlands is even more limited, apart from a handful of examples showing that tree densities are lower and habitat development slower than in planted woodlands. Despite the scarcity of scientific evidence, there is a fairly generalised assumption that naturally created woodlands will be more structurally diverse and ecologically complex than planted sites, which usually have a more uniform structure (e.g. with trees of similar ages and sizes planted in evenly-spaced rows). Natural colonisation also maintains local tree genotypes and high genetic diversity which can increase resilience to future changes in environmental conditions. Additionally, naturally established woodlands are more exposed to natural selection processes than planted trees which have often been commercially grown and kept in more controlled environments. For these reasons, natural colonisation is likely to enable local adaptation to climate change and confer higher resilience to other disturbances such as tree disease and pests. BLENDED APPROACHES Th benefits and challenges of planting and natural colonisation suggest that these alternative approaches are each likely to be better suited to particular objectives; for example, tree planting would likely be the preferred approach for land managers interested in timber production, whilst the more naturalistic appearance resulting from natural colonisation may be more appealing to those interested in restoring biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. But whilst there is often debate and polarisation between the use of these approaches, tree planting and natural colonisation exist at two ends of a continuum and may be used in complementary and blended combinations across a landscape, depending on the local conditions and the benefits expected. For example, some initial degree of planting can assist natural processes by enhancing seed dispersal and ameliorating the local environment; this can be done through low-density planting or by planting small clusters of trees (also known as nucleation planting) to provide perches for seed-dispersing birds and a future local seed source once the trees themselves reach seed-bearing age. In naturally colonised woodlands, supplementary or enrichment planting can also be used to increase stocking densities and to introduce species which are otherwise slower to colonise. Combining approaches will bring attributes of each method. The balance between approaches should depend on site factors and management objectives. The Woodland Trust – the largest UK woodland conservation charity – recommend to always include natural colonisation in woodland creation plans wherever possible, either as primary method or as a component alongside planting. However, much of the existing evidence on blended approaches is drawn from regions with quicker habitat successional rates such as the tropics, where landscapes have not been as heavily degraded as in the UK. PERCEPTIONS AND OBJECTIVES Attitudes of land managers towards woodland creation are central to meeting government woodland expansion targets, as most land is in private ownership and managed primarily to meet their objectives. However, we have a poor understanding of land managers’ attitudes towards woodland creation approaches other than tree planting, and it is not clear which kinds of land managers do, or would, engage with woodland creation through alternative approaches incorporating natural colonisation, and why. This is likely to be influenced by the objectives that different land managers hold for their landholdings and woodlands, by their cultural identities (what they see themselves as, e.g. conservation manager, farmer, forester), and by their level of understanding of the likely outcomes and risks associated with different woodland expansion approaches. THE TREE_PLANAT PROJECT TreE_PlaNat (Treescape Expansion through Planting and Natural Colonisation) is an interdisciplinary project comprising ecologists and social scientists at the Universities of Stirling, Edinburgh and Royal Holloway, and Forest Research, in partnership with the Woodland Trust and National Forest, charities at the forefront of practical woodland creation and management activities. Our overall aim is to assess stakeholder perceptions and socio-ecological consequences of woodland expansion approaches spanning the planting to natural colonisation continuum. Specifically, in TreE_PlaNat we will explore the attitudes (e.g. perceived risks and benefits) of a diverse range of land managers towards woodland creation strategies spanning the planting to natural colonisation continuum, and explore how these vary with their objectives, socio-economic and ecological context. We will do this through a combination of broad surveys and in-depth interviews encompassing a diversity of agricultural land managers within the private (e.g. farmers, foresters and woodland managers), public (e.g. Forestry England) and third sectors (e.g. environmental NGOs). We will also quantify various socio-ecological outcomes of woodland creation approaches spanning the planting to natural colonisation continuum, which we have identified as of key interest to agricultural land managers during our scoping work and in consultation with our project partners. These include for example biodiversity benefits, ecological function, resilience, people’s well-being and income potential. We will quantify these using a combination of state-of-the-art technologies (such as LiDAR and acoustic monitoring) and more conventional field surveying methods in 35 woodlands created in recent decades through a range of approaches: purely using natural colonisation, combining natural colonisation and planting, or predominantly through planting alone (we have identified these sites using a combination of historic maps, Woodland Grant Scheme datasets and aerial photography). Finally, we will integrate our socio-ecological findings to better understand the links between land managers' perceptions and objectives, the approaches they use to create woodlands, and the socio-ecological outcomes derived from woodland creation spanning the planting to natural colonisation continuum. We will also deliver a coordinated timetable of activities and outputs – including webinars, blogs and capacity building events – to demonstrate how tree planting and natural colonisation can be used in combination to scale-up woodland expansion for a range of objectives on agricultural land. We will also assemble of a board of knowledge users to discuss knowledge needs, reflect on the relevance of our findings, provide feedback on planned knowledge exchange activities, and identify opportunities for quick wins and strategies for sustained impact. Stay tuned to keep up to date with our journey! CITED LITERATURE: [1] Forestry Commission (2021) Using natural colonisation for the creation of new woodland. [2] Herbert et al. (2022) Woodland creation guide, Woodland Trust. [3] Fuentes-Montemayor et al. (2021) The long-term development of temperate woodland creation sites: from tree saplings to mature woodlands. Forestry 95: 28–37. [4] Broughton et al. (2021) Long-term woodland restoration on lowland farmland through passive rewilding. PLOS ONE. |

AuthorsLaura Braunholtz, Ecology post-doc, University of Stirling Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed