|

By Maddy Pearson, Forest Research On a sweltering Thursday in June, we headed to the Hall Farm Estate on the southern fringe of Dartmoor. We were a small team of two social scientists and one ecologist from Forest Research. Our visit was an opportunity to engage with colleagues from the Forestry Commission and The Woodland Trust on the topic of natural colonisation. Chauffeured by a Forestry Commission colleague, we weaved through country lanes, admiring overhanging trees and rolling hills before arriving at a picturesque farmhouse. The farm and its woodland were steeped in history, having been home to The Woodland Trust’s founder Ken Watkins during the Trust’s inception. In recent history the farm had been in private ownership, but has this year been bought back by the Woodland Trust. Dave Rickwood, The Woodland Trust’s site manager for Dartmoor, explained that the Trust are looking into an England Woodland Creation Offer (EWCO) grant to undertake natural colonisation on the Hall Farm Estate.

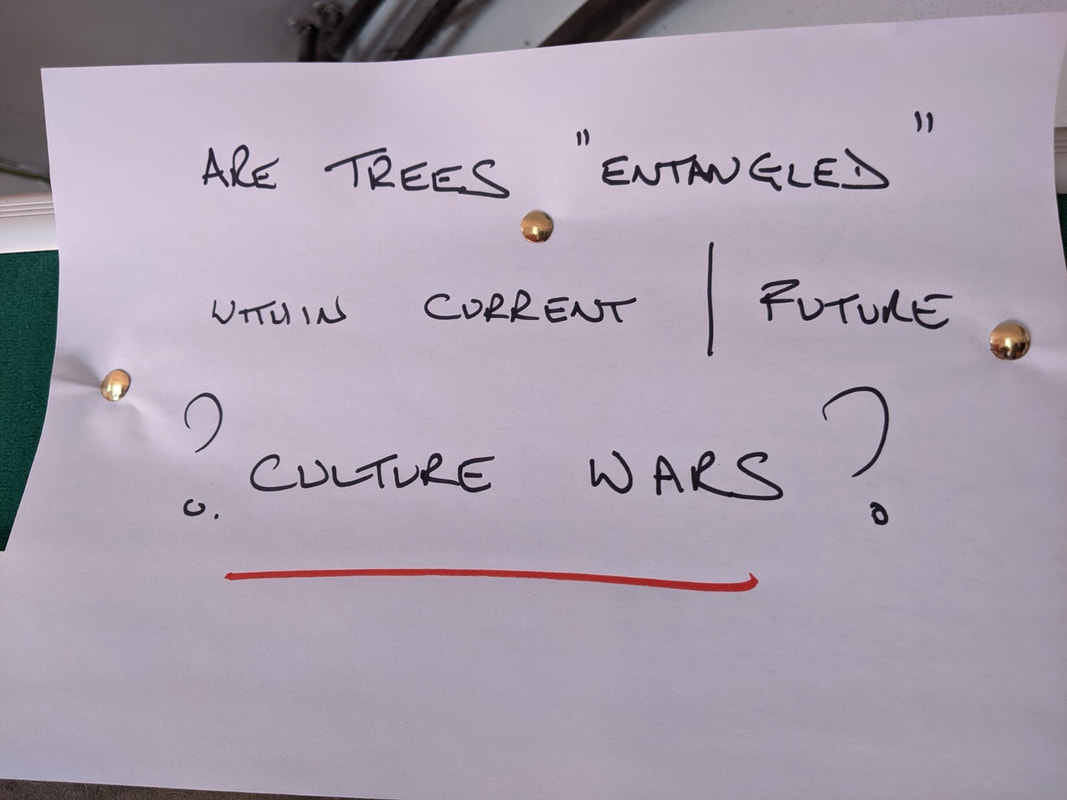

A final piece of paper caught the eye of one of the researchers. In black felt-tip pen the text asked of the reader, “Are trees “entangled” with current/future culture wars?” This is certainly a question worthy of attention, and not only for the social scientists among us. Tree cover expansion as an ecological process can never be separate from the socio-cultural, the economic, or from the wider environmental politics of the day, and this must be recognised and taken seriously if national aims are to be met. How should land be used? How should the climate crisis be responded to? These are the kinds of questions that emerge in present-day culture wars, and are the questions to which tree cover expansion can be considered “entangled”. Presenting our researchBefore heading out to see natural colonisation beside the estate, we presented some of our research to date, and introduced questions we will be exploring over the next year. As well as the importance land managers place on outcome uncertainty when weighing up whether to use tree planting or natural colonisation as tree cover expansion strategies, we landed on the importance of language and communication. Recognising that uptake of grants for natural colonisation has been low, and that natural colonisation as a term is not commonly used by land managers, we asked attendees on the visit to consider how language and communication might be impacting the tree expansion strategies taken up by land managers they work with. With this provocation in place, the group of attendees, as well as three eager dogs, headed out of the barn to see some trees! Heading up the hillWe were led away from the barn through the farm to see examples of natural colonisation on Yadsworthy farm. We took in the tree cover that was gradually creeping up the hill and were asked to estimate, for a big reveal later in the day, how long it had taken for this colonisation to occur. Asked about any pressures on natural colonisation in this area, Dave explained that periodic grazing is used in the field to trample any unwanted vegetation. He said mortality is good given low deer pressure in the area, although he did explain that this is changing as these colonised fields are starting to provide optimum habitat for deer, and thus they are starting to see higher numbers appear. To Dave’s surprise he has even spotted red deer recently. This observation really brought home that natural colonisation is part of more-than-human assemblages that are dynamic and will continue to change as tree cover increases. We continued on up to the fringe of Dartmoor national park and Dave shared an interesting finding with us from a researcher at Plymouth University. This professor has estimated that for woodland expansion to occur on the commons of Dartmoor, 8 years of no grazing would need to be secured. Grazing pressure is just one of the many things landowners weigh up when deciding on woodland expansion strategies. Where it all beganAfter a short lunch pitstop back at the barn we headed out of the farm in the opposite direction to see the natural colonisation that had been making its way up the hillside from the viewpoint of its seed source. We walked along a country lane, turning sharply left onto a narrow footpath that allowed us to walk beside the River Erme. We came to a standstill a few minutes later underneath the riparian woodland, listening to the sound of water cascading through the channel below us and noting how inviting this river looked given the hot weather. Dave explained that a variety of trees were colonising the land from this riparian strip up the hill, including Sessile oak, hawthorn, holly, hazel, rowan, sycamore, beech, alder buckthorn. Having waited in anticipation, Kevin explained to the group how long it had taken natural colonisation to reach this level of maturity. Using maps and aerial footage from the post-World War Two period, the team of spatial scientists at Forest Research had estimated that natural colonisation had taken about seventy years to reach its current state. We all agreed that while the tree cover was impressive this was quite a long time! The time it takes for natural colonisation to establish has emerged as an area of concern across land manager groups and this example certainly spoke to concerns that establishment could take longer than a human lifetime. That said, standing among the plush trees you couldn’t help but be struck by the diversity and beauty of this naturally colonised space and see the appeal of using such strategies.

We walked back up to the house, discussing our research and planning to follow up with some new faces we had met. It was a stimulating and thought-provoking day out, one that sparked conversation in the car back to Plymouth around what kind of site we might like to see next. We wondered about a visit to a site where natural colonisation has been given the green light but is yet to begin. Or, we thought it might be interesting to visit a site where natural colonisation had failed. We sunk back into the warm seats of the car and decided it was a decision for another day.

2 Comments

Emma Dear

9/6/2023 09:36:58 am

70 years is a long time. I'd love to hear a blog on what the team thinks might be the advantages of the slow establishment vs fast. Can you achieve the same result? Maybe your next visit should be a compare and contrast 70 year old mixed broadleaf planted woodland?

Reply

Huw Davies

9/7/2023 01:45:42 am

Great article - thanks for posting.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsLaura Braunholtz, Ecology post-doc, University of Stirling Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed